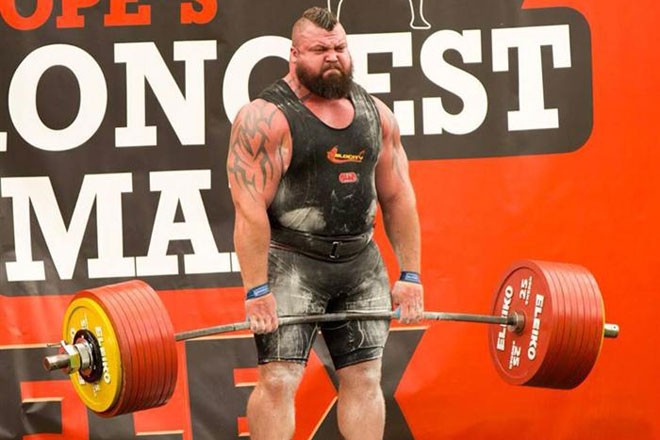

*Photo Credit: Eddie Hall – world record holder with a 1020lb deadlift

If you’ve been following my writing for a while, you’ll remember I made a post awhile back where I said, “the squat is the best exercise in the history of ever.”

Well, my thoughts on that haven’t changed.

I still think the squat is the best exercise, and that has a little to do with the fact that squats build a tremendous amount of strength and size in the lower body – as well as improve athleticism, coordination, and burn a crap ton of calories – and a lot to do with the fact that squats are what I enjoy and feel I’m best at.

Hey, I’m a bit biased.

But, I’m also open-minded enough to realize that there are other exercises that are just as awesome as the squat (well, almost as awesome).

And one of those exercises is the deadlift.

If the Squat is Batman, the Deadlift is the Joker

Batman always gets the best of the Joker, but it’s only by a slight margin and isn’t because the Joker isn’t just as powerful or super intelligent (good always conquers evil…you know that).

In regards to strength training, the deadlift has just as much capacity to develop strength, size, athleticism, and help you burn calories and lose body fat as the squat.

It just does so in different ways (it’s a hip-hinge pattern instead of a squatting pattern, and it places a bit more emphasis on the posterior chain than it does on the anterior chain).

And, for some, it does so in better ways.

I’m not saying you HAVE to deadlift.

Seriously, you can get by without it.

I’m just saying if you do deadlift, it’ll turn you in to an all-around badass.

How Do I Perform a Deadlift?

It would be much easier to show you – some good videos on deadlift technique (conventional and sumo) can be found HERE and HERE – but some common cues I like to give clients are as follows:

- Think about pushing rather than pulling.

This is a tip I got from my buddy Eric Temple. Although the movement is called a “pull,” you want to PUSH as hard as possible and generate the majority of your force from your legs (instead of your low back). Not only will this help you lift more weight, but it’ll also decrease the strain on your low back, and help prevent injury.

- Brace HARD.

A good way to think about bracing is it’s the tightness you create in your abs when you’re about to get punched in the stomach. You want to fill up your belly, low back, and sides with air, and then brace as hard as possible. MAINTAIN this brace throughout the duration of the lift (this will create a ton of stability and help you maintain a good position).

- Keep your hips high-ish.

They shouldn’t be excessively high, and hip position will change based on the lifter, the type of deadlift they’re performing, and what they feel is the most comfortable, safe, and strong starting position. But, the deadlift is NOT A SQUAT, and you should not be squatting down to the bar when setting up for the deadlift. When you go to grab the bar, think about shooting your butt back and down towards the wall behind you. This will load your glutes and hamstrings, and make sure that your hips are performing the majority of the lift.

- Hump the bar.

Sounds crazy, I know, but you don’t want to finish the lift by arching your low back. When the bar passes your knees, squeeze your glutes as hard as possible. My buddy Adam Pine likes the phrase “act like you’re cracking a walnut in between your ass cheeks.” Doing so will not only enhance hip drive and increase the chances of you completing the lift (as opposed to failing at lockout), but again, it’ll help prevent injury.

- Stand up.

At the most basic level, that’s all you have to do. Make sure you’re in a good starting position, get tight, and then…JUST STAND UP.

Now that you have a better understanding of the technical side of the deadlift, lets go over various types and what they’re good for.

– Conventional Deadlift

*Photo Credit: Bret Contreras

A conventional deadlift is the “traditional” deadlift so to speak. All deadlifts place a tremendous amount of stress on the glutes, hamstrings, lower and upper back, and forearms (grip), but the conventional deadlift places more stress on the low back and quads than the sumo deadlift. It’s the most technical deadlift variation (for most people), and requires a good amount of motor control, mobility (ankle, hip, and t-spine), and stability to perform.

– Sumo Deadlift

*Photo Credit: Bret Contreras…Again

The sumo deadlift places more emphasis on the hips because of the wider stance and externally rotated – and abducted – hip position. Because of the more upright torso, it places less stress on the low back. It’s less technical than the conventional deadlift (and is therefore usually easier to learn), but requires an extreme amount of hip mobility to perform properly.

– Trap-bar Deadlift

*Photo Credit: Christian Thibideau

The trap bar deadlift is the least technical deadlift variation, and is easier to perform because the weight is aligned with your center of gravity (which makes it a combination of a deadlift and a squat). It places a bit more emphasis on your quads because of the lower hip position (and consequential knee bend), and tends to put less stress on your low back than the conventional deadlift.

– Romanian Deadlift (RDL)

*Photo Credit: Scott Herman

A RDL is a conventional deadlift where you DON’T lower the bar all the way down to the ground (you lower down to mid-shin). Because you’re not going all the way down to the ground, more movement comes from the hips as opposed to the knees (the knee position doesn’t really change at all), which allows you to get a much greater stretch in the hamstrings (and therefore place more stress on them).

– Block Pull

*Photo Credit: Dan Green

A block pull is an “elevated” deadlift. You choose any of the first three deadlift deadlift variations (conventional, sumo, or trap-bar), and perform it elevated on blocks, weight plates, or in a power rack (it then becomes a “rack pull”). Doing so shortens the range of motion, which allows you to either 1.) Overload the movement, 2.) Target specific weak points in the range of motion, or 3.) Learn how to deadlift in a good position before gradually working your way down to the ground.

– Deficit Deadlift

*Photo Credit: Tim Thebodeau

The complete opposite of a block pull, the deficit deadlift is a deadlift variation where YOU’RE elevated, and the deadlift bar remains on the ground. This increases the range of motion, making the lift significantly harder. Training the deficit deadlift for awhile will 1.) Make it easier when you go back to normal range of motion deadlifts, and 2.) Increase your strength off of the floor.

Which Deadlift Variation Should I Choose?

There are a couple ways to think about this.

I would recommend asking yourself these three basic questions:

- Am I a powerlifter?

If you are, you’ll have to spend AT LEAST a small amount of your training time performing either the sumo or conventional deadlift.

That’s because they’re competition lifts, and you need to not only build – but also practice – those lifts if you expect to perform them well in competition.

If you’re not a powerlifter, you don’t have to train the sumo or conventional deadlift.

They’re extremely beneficial – and you probably should perform them if you have the capacity to do so – but…it’s not a necessity.

- Do any of the deadlift variations cause me pain?

There are a lot of factors that play in to this – individual anatomy, injury history, current mobility/stability levels, etc. – but if a deadlift variation causes you pain, it’s probably not a variation you should be performing (at least not right now).

- Which deadlift variation am I best at?

Everyone has a deadlift variation they feel most comfortable with and can lift the most weight on.

Figure out which variation that is, and make it your priority.

How Often Should I Switch Variations?

In my opinion, every 4-12 weeks.

You don’t have to do this (it’s not a necessity).

But, doing so will:

- Allow you to bring up weak points or re-emphasize strong points.

- Prevent overuse injuries.

- Provide a new stimulus (which should spark new growth).

- Break up the monotony of training (i.e. make things less boring).

Cool…So How Should I Program the Deadlift?

Begin by following these guidelines:

- Stick to 3-6 sets of 1-6 reps with the sumo, conventional, or trap-bar deadlift (as well as deficit deads and block pulls), and 3-6 sets of 5-12 reps with RDLs.

- Perform the deadlift 1-2x per week.

- Perform the deadlift first or second in a workout (The most technical and taxing exercises come first).

- Choose one deadlift variation to focus on for a training cycle (sumo, conventional, or trap-bar in most cases), and then choose accessory exercises to help build them (block pulls, deficit pulls, RDLs).

- Try to add load (5-20lbs) or sets on a weekly to monthly basis.

These guidelines are just starting points…and you’ll have to make adjustments based on your results.

Strength training is – and always will be – a game of trial and error.

If something’s working, keep doing it.

And if it’s not working – or stops working – switch to something else.

Like What You See?

Get the Smoot Fitness Guide to Getting Stronger - FREE.

Leave a Reply